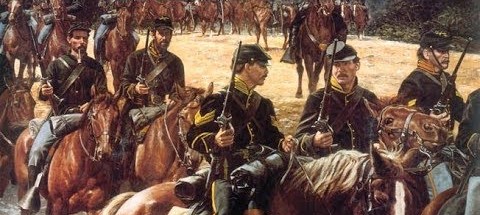

Captain John Henry Peters was 34 that Monday afternoon, of 18 May, 1863. And as he boldly galloped northward across the rolling hills of central Mississippi, he knew he was doing the greatest thing he would ever do, leading 27 men, volunteers all from company B of the 4th Iowa cavalry – 24 enlisted men and 3 officers – on a great adventure. Death might be waiting over the next rise. But until then, they were masters of their own fate, and possibly the fate of every soldier in this war.

The only delay in their progress were the occasional stragglers in butternut brown or tattered gray they paused to disarm. They took the soldier's weapons and told the wounded and weary to go home. And then the blue clad knights galloped off, leaving a psychic havoc on their wake. Those they had randomly touched were offered the choice between devotion to duty or to their family, between a form of volunteer slavery and freedom. The individual consequences were of no concern to the troopers, until they fell upon a single sad rebel soldier seeking to escape on a sad horse. With a half dozen Navy Colts pointed at him the man quickly surrendered his weapon. Then, when he realized they were soldiers from Iowa, joy flashed across his face.

He was from the village of Green Isle, Iowa, the prisoner proudly explained. Sheltered in the deep shadows of high bluffs along the Mississippi River – the village only received an hour of winter's sunlight - Green Isle had been one of the first Irish Catholic footholds in the Hawkeye state. The romance of the riverboats which paused there to pickup fire wood had enticed the young rebel to sail down the river, where he had been caught when the war broke out. Drafted into Confederate service, this was his first chance to escape. Or so he said. And, if the captain would write him a pass through the Union lines, so he could get to St. Louis, he promised to show the Yankees a back road into the fortifications atop Snyder's bluff. As that was exactly where they were heading, Captain Peters accepted the offer.

Born in Pennsylvania, John Peters was a life long Democrat. In his early twenties he spent 2 years in the Yellow Fever and malaria incubator of Cuba, “for his health”. During those years he had studied law, and returned to “the states” in 1852 to pass the bar under a lawyer in Freeport, Illinois. He married a local girl, Helen Kneeland, and the next year the new lawyer and wife moved to the tiny Delaware County seat of Delhi, Iowa. Three sons later, in September of 1861, at Camp Harlan near Mount Pleasant, John signed a three year enlistment as an officer in the 4th Iowa volunteer cavalry regiment, and promptly rode off to war.

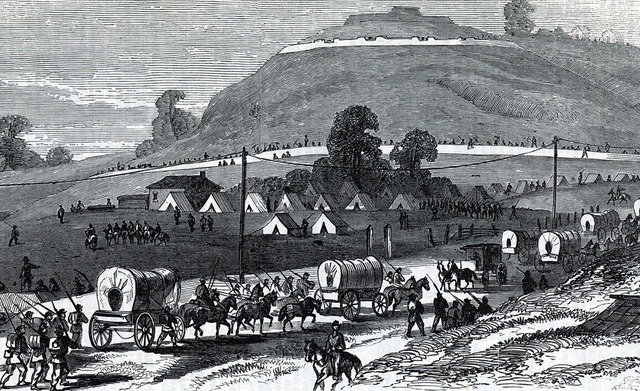

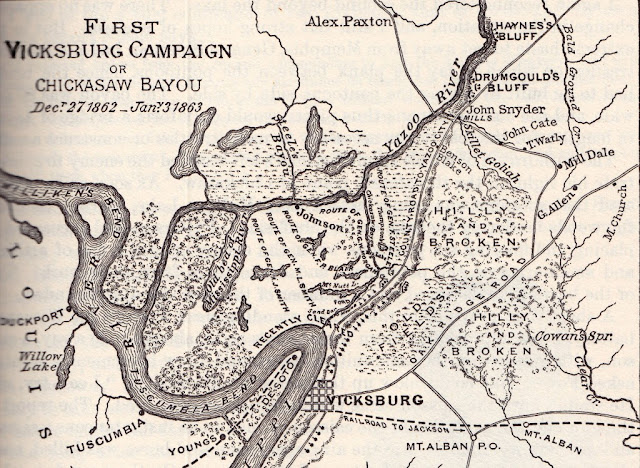

Snyder's bluff (above) was a 900 foot tall spike in the Walnut hills, towering above the head of Chickasaw Bayou, on the Yazoo River. The previous December this had been the edifice which blocked Sherman's attempt to sneak in the back door of Vicksburg. But everything Grant's army had done over the next 5 months, the tons of mud moved in the Lake Providence canal, the sweat and exhaustion in the Yazoo and Steeles Bayou expeditions, the horror of running the Vicksburg batteries, the risks endured by Grierson's troopers, the landing at Bruinisburg, the battles of Port Gibson, of Raymond, of Jackson, of Champion Hill and the Big Black River Bridge, had all been endured just to clamber those last 100 yards to the crest of the Walnut Hills, to break through the back gate of Vicksburg.

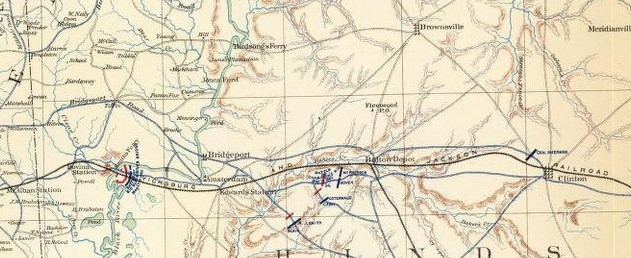

Both Sherman and Grant assumed they were going to have to fight the 3,500 man garrison at Snyder's Bluff (above, left) , as well as the 4,000 men which spies reported were encamped along the Brownsville Road. So when Sherman dispatched the 4th Iowa that morning from the Marshal Plantation, their orders were to merely report rebel activity on the Brownsville road heading north out of Vicksburg. Talking this road would give Sherman, “ command of the peninsula between the Yazoo River and Big Black.”

They set off just after dawn up the Bridgeport Road to the village of Tucker (above, center left), where they turned north toward the Oak Ridge Road. About noon they reached the Oak Ridge Post Office, and here they halted. An officers' conference was almost unanimous in deciding not to alert the rebels to their presence. Captain Peters was the sole vote for continuing. The column set on a reverse march. But Peters so pestered his commander, Colonel Simon Swan, that Peters was reluctantly allowed proceed with a squadron to Snyder's Bluff and report what he found.

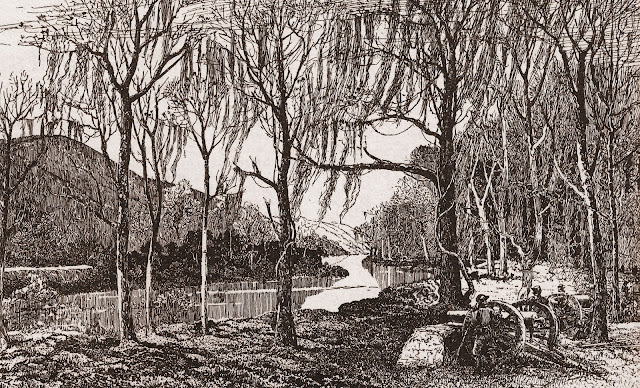

What Captain Peters found was stunning. He wrote later, “At about three fourths of the way to the summit we came out into a broad military road that wound around into and above the works...Before us lay the broad Yazoo and from the landing up to our very feet lay...the most complete and strongest fortification of the whole Mississippi valley.” At a walk they entered the fortifications, unchallenged by a single sentry. In a ring around the steep slopes of the bluff were the 11 ugly black cannon in their emplacements - two 8 inch Columbiads, three 24 pounders, two 32 pounders and two heavy 12 pounders, all connected by trenches and fire pits for infantry. But the gunners were nowhere to be seen, nor were the infantry.

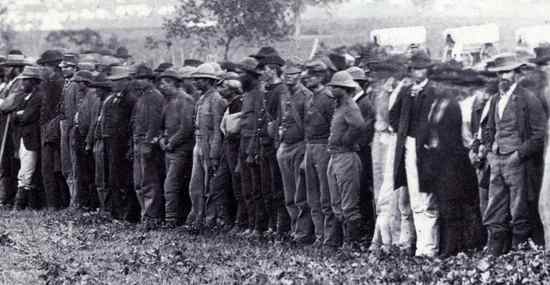

Continued the captain, “We rode forward expecting every minute a demonstration that would send us back at a livelier pace than we had come in. All at once there poured out a squad of armed soldiers from a large commissary building...25 or 30 in number, and undertook to form a line in our front. In a moment the order came “Left front into line. Draw sabres! Charge!” and in a moment we were down upon them. Not a gun was fired nor a serious saber stroke given. They simply threw down there arms and surrendered. From the Sargent in command I learned that the fortifications had been evacuated the night before.”

In fact the garrison -the 3rd Louisiana Infantry regiment - had marched for Vicksburg, carrying all the food and supplies they could. A remaining pile of corn was left on the landing in front of the bluff, supporting the new prisoners contention that 43 year old Brigadier General Louis Hebert and his men would be returning in the morning. This was given added weight when Peters noted that barbed steel spikes had been driven into the touch or vent holes of many of the heavy cannon left behind, which prevented them from being fired until the spikes were removed. Those which had not been “spiked” were triple loaded with shot and shell, ensuring they would explode if the Yankees tried to fire them. Peters knew he could not hold the position with 2 dozen troopers. And it would be a race to return to Union lines and get back with enough infantry to hold the position. Luckily for Captain Peters there were Union soldiers much closer.

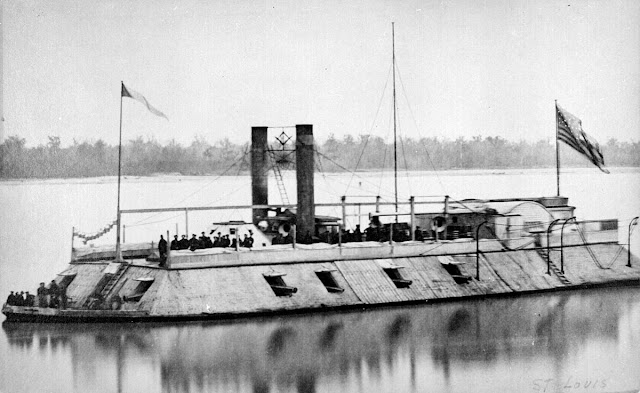

Using his binoculars, Captain Peters could see Federal Navy gunboats and ironclads anchored in the mouth of the Yazoo, less than 2 miles away. So after sending his prisoners to the landing under guard, Peters, “sent a man to the top of the bluff with a fairly clean towel that I happened to find in my saddle pocket to try and signal a gunboat...I could plainly see a squad of officers on the deck with their glasses pointed in our direction but making no effort to communicate with us. I then directed Lieutenant Clark to take a couple of men and follow down the river bank until he could communicate with the boat.”

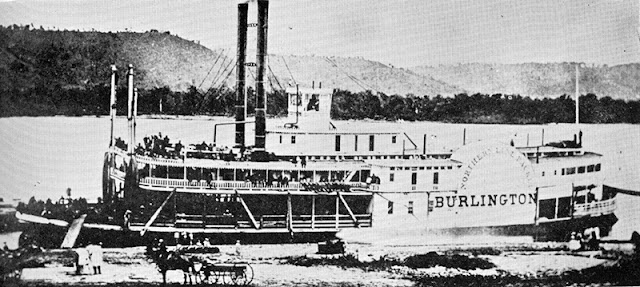

A few hours later Peters was, “...taken from the saddle and carried to the officer's mess room (on the USS Baron De Kalbe) (above). The prospects of a good supper after a fast of 12 or 14 hours and a ride of over 20 miles...settled the question and I became the guest of the Captain, and did ample justice to a splendid supper with all the et cetera....after signaling an orderly boat and preparing a message to our fleet of transports....notifying them... that the Yazoo was open up to Chickasaw Bayou, we climbed upon the backs of our hungry and tired horses and rode rapidly back toward the place we had left..”.

and the gun boats dropped anchor, to defend them. The troopers from Iowa reached their own lines after midnight, “to the utter surprise and great joy of our whole command”, said Peters. And by 2:00am, on Tuesday, 19, May, 1863, Grant and Sherman were informed they had reestablished communications with the U.S. Navy, and their supply line. The back door to Vicksburg (below), had been kicked wide open.

- 30 -